Bankside

Today, the south bank of the Thames below the City of London is a vibrant, bustling place beloved of tourists. It is home to the Tate Modern art gallery, Sam Wannamaker’s wonderful recreation of Shakespeare’s Globe theatre, and the Southbank Centre. Most of those who live or visit there are impeccably law abiding. It wasn’t always like that.

Bankside was once known at The Turkish Shore, a reflection of the distinctly rebellious and exotic attractions it offered. Southwark, then the 26th ward of the city, was a collection of manors termed “liberties”, because the laws of the Mayor of London and the Corporation did not run there. It was a place of brothels (known as stews), taverns, dice-dens, play-houses and bear-baiting rings. Henry II was just one of a series of monarchs who tried to restrain its excesses, with little success. A parliament held in the eighth year of his reign decreed, amongst other prohibitions, that no stew-holder should allow any woman of religion, or any man’s wife to solicit from their premises. On the river-facing side of their stews, the owners painted garish signs to attract the sailors from the many ships moored on the river, and any citizen across the single bridge connecting the two banks who might care to risk his safety and his purse for the entertainments on offer.

London Bridge was already famous well beyond the shores of England. By Nicholas and Bianca’s time it had already stood for centuries, and was now more of a busy street lined with houses than a bridge. If the thrills of the flesh available once through the southern gatehouse were too rich for you, you could always raise your heartbeat by “shooting the bridge” – a sixteenth-century theme-park ride in which the oarsman of the boat you had hired would plunge you between the great stone “starlings” that supported the thoroughfare above. After that, if you still had a mind for spectacle, and a stomach still to churn, you could stroll across to the gatehouse, where - if you cared to glance up, you could view the rotting heads of traitors impaled on spikes set around the parapet. Then off the playhouses: the Rose, the Swan, and – by 1599 - the Globe.

It is surprising, therefore, to learn that the Bishop of Winchester owned so much of the land on which Bankside was built, though perhaps not that the women who plied their trade there were known as “Winchester Geese”. Raffishly Elizabethan though all this sounds, it should not be overlooked that the lives of the women who worked in the stews was brutal, prone to violence and disease, and usually life-shortening. Bankside could often be a very dark place indeed.

Nonsuch

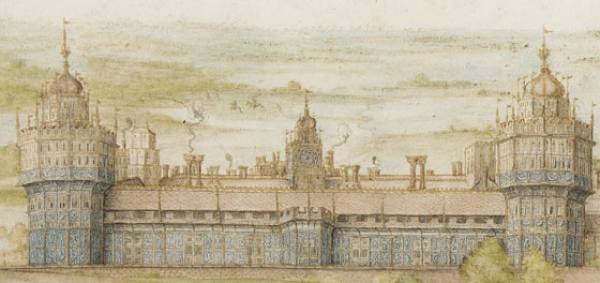

If Bankside represents one face of Elizabethan England, the great palace of Nonsuch at Ewell in Surrey can stand for the other. It is a tragedy that it no longer exists, because if it did, it would be one of the finest examples of a Renaissance palace to be seen anywhere in Europe.

Commissioned by Henry VIII to be a palace rivalled by “none such”, work began in the spring of 1538. By the time Nicholas Shelby passes through the magnificent outer gatehouse, it is no longer in royal hands. The palace was sold by Henry’s daughter, Mary, to the Earl of Arundel, passing to John Lumley, his son-in-law upon his death. The library that Lumley established there was considered the equal of any university library existing in England.

In 1592 Nonsuch reverted to being a royal place, when Lumley surrendered it to Elizabeth 1 in payment of the huge debts he owed to the Crown. It was at Nonsuch, where Elizabeth had played as a child, that Robert Devereux, the Earl of Essex, burst into her private chamber on his precipitous return from Ireland in 1599, encountering his aging monarch without her wig and make-up - an intrusion for which she never forgave him.

In the seventeenth century, Charles II gave the place to one of his mistresses, who had it demolished to pay off her own debts. It remained almost forgotten, until the foundations were excavated in 1959. Fortunately, some of Lumley’s library survived and is to be found in the British Library.