They say that when writing a thriller or a crime story your hero should be expert in what they do. James Bond is not just a secret agent, he’s the best secret agent. Villanelle may be the baddy, but she’s terrifyingly competent at her chosen profession. The problem the writer of historical thrillers and mysteries faces is that there are relatively few areas your lead character can be really good in that will appeal to a modern reader. I thought that making my lead character a soldier was too predictable, but skill at dancing a pavane or playing the lute don’t lend themselves to high drama. Medicine seemed a good possibility, but for the fact that most of what physicians in the sixteenth century thought they knew about medicine was utterly wrong.

But that in itself offered two useful possibilities. The first was that it presented a perfect point of conflict for my protagonist: a life-changing one that Dr Nicholas Shelby must face. So I made him a brilliant practical surgeon (having honed his skill on battlefields in the Spanish Netherlands) but then made him face the realisation that what he thinks he knows about the rest of medicine is built on little more than quicksand. And it can’t help those he loves when they have most need of it.

The other benefit was this: it allowed me to write about an Elizabethan doctor without knowing more than the average layman about modern medicine!

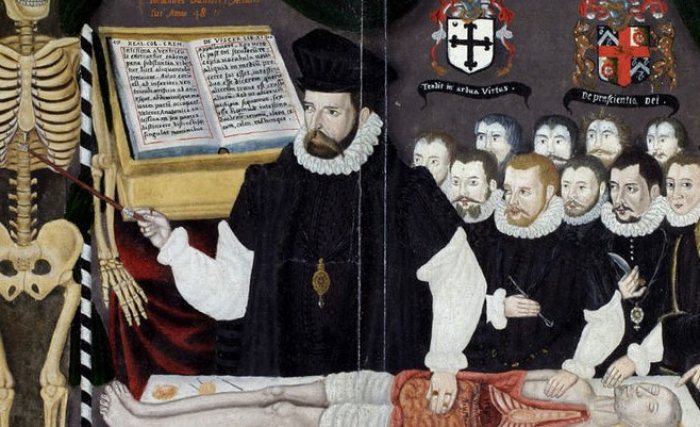

Nicholas Shelby stands on that dramatic fault-line of the sixteenth century world: the growing tension between the ancient and the modern, between the teachings of antiquity that most physicians of the time took to be set in stone, and the emergence of the new sciences, the first ripples in what would become the tsunami of the Enlightenment. When we first meet Nicholas, in 1590, no one knows how the circulation of blood around the body works. But William Harvey, who will publish his world-changing discovery barely three decades in the future, is already studying at Cambridge.

The old world is Bianca Merton’s. Her skills are those of the traditional healer: her knowledge of herbs and plants. Hers is the ancient wisdom of the “wise woman”. Yet often it is Bianca who propels Nicholas forward. She is the more intuitive of the two. And more practical. I have the notion that when the series concludes, she will have established a network of apothecary shops across London, named after her favourite footwear – Boots.